COVID-19 Screening Kiosk

COVID-19 Screening Kiosk (2022)

Why an Automated Screening Kiosk?

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed a weakness in how public spaces handle health screening: manual temperature checks, visual inspection for mask compliance, and ad-hoc sanitization. These processes are slow, labor-intensive, error-prone, and increase close-contact exposure. At the same time, large-scale diagnostic testing is too expensive and impractical for continuous use. This project targets the gap: a fast, reliable first-line screening system that flags potential risk while maintaining social distancing.

The goal was to design and build an automated, self-service screening kiosk capable of rapidly assessing key COVID-19 indicators (mask usage, body temperature, blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂), and pulse rate) while minimizing physical contact and human intervention. The system needed to be accurate enough to be meaningful, fast enough to avoid bottlenecks, accessible to a wide range of users, and inexpensive enough to justify real-world deployment.

Rather than treating this as a purely machine learning or sensing problem, I approached it as a full systems challenge: integrating sensing theory, signal processing, computer vision, embedded hardware, user interface design, accessibility standards, and cost analysis into a single deployable platform.

This kiosk was developed as part of my bachelor’s thesis and internship at ETH Zurich, with the broader vision that such systems could extend beyond COVID-19 and serve as scalable screening tools for future infectious diseases and public health emergencies.

Demo

High Level Overview

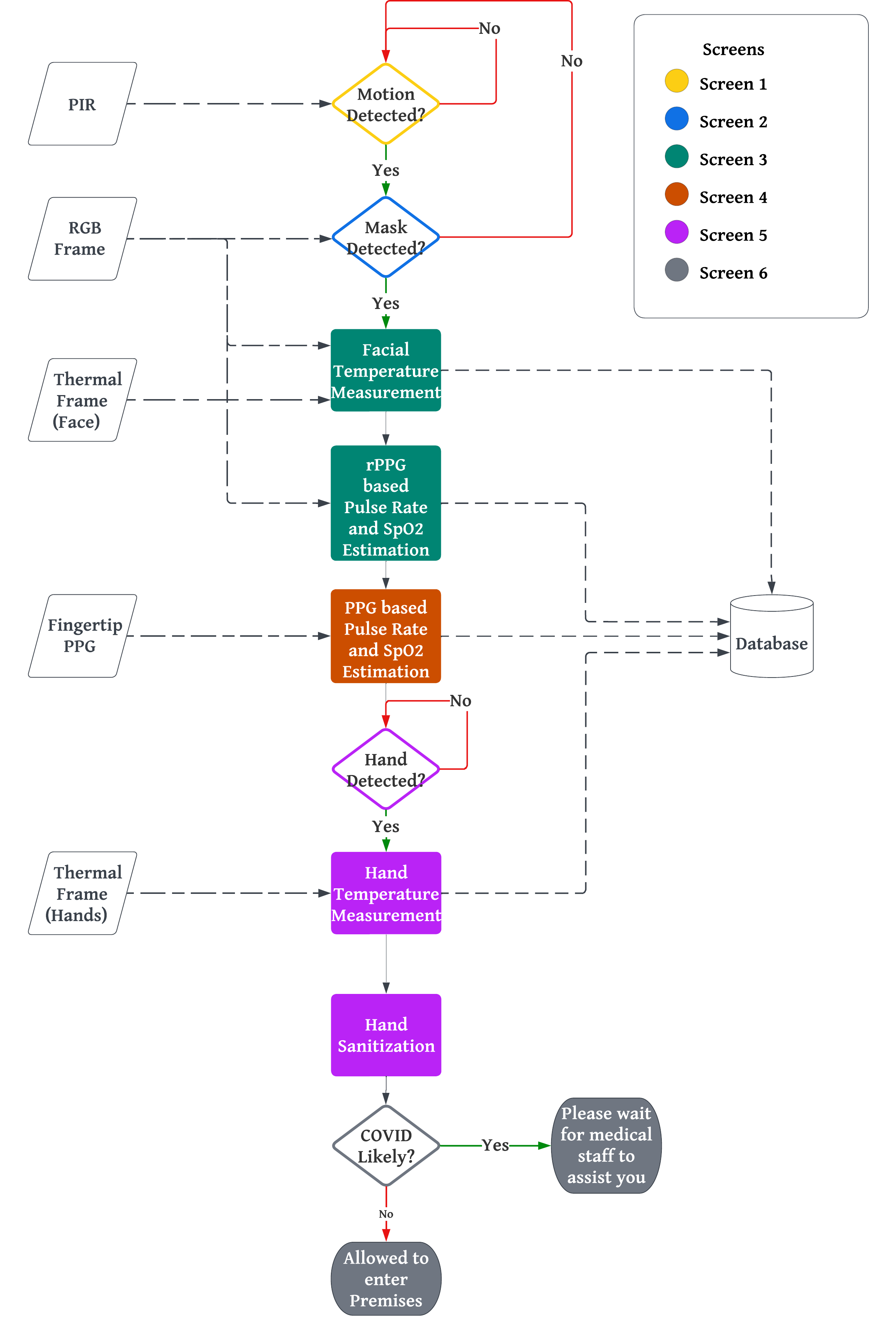

At a high level, the kiosk is designed to perform end-to-end health screening for a single user in a guided, self-service workflow. From the moment a user approaches the kiosk to the final screening decision, all sensing, inference, and feedback are handled automatically without requiring trained personnel.

The system integrates multiple sensing modalities (vision, thermal/infrared sensing, and photoplethysmography), each targeting a specific screening signal. These subsystems operate in parallel and are orchestrated through a centralized decision-making pipeline to minimize total screening time.

Screening Signals Captured

The kiosk screens for the following indicators:

- Mask compliance using an RGB camera and a real-time computer vision model

- Body temperature using thermal/infrared sensing with vision-based alignment

- Blood oxygen saturation (SpO₂) using a fingertip photoplethysmography (PPG) sensor

- Pulse rate, estimated from both contact-based PPG and camera-based remote PPG (rPPG)

- Hand sanitization, enforced as part of the workflow to reduce cross-user contamination

Each signal is chosen deliberately; no single measurement is sufficient to identify infection.

User-Centered Workflow

The kiosk guides the user through the screening process step by step using a touch-based graphical interface, visual indicators, and audio cues. The workflow is designed to be:

- Fast: All measurements are completed within a single interaction

- Low-contact: Sensors are either contactless or require minimal touch

- Accessible: Physical dimensions and interface design follow established accessibility standards

- Error-tolerant: The system detects improper positioning or incomplete steps and prompts corrective action

Importantly, the user is never required to interpret raw data. The kiosk abstracts sensor complexity behind simple instructions and produces a clear screening outcome at the end of the interaction.

System Architecture Philosophy

Rather than building a monolithic pipeline, the kiosk is structured as a set of loosely coupled subsystems:

- Independent sensing modules acquire raw data

- Signal processing and inference run concurrently

- A central controller synchronizes results and enforces decision logic

This modular design improves robustness, allows individual components to be upgraded independently, and makes the system adaptable to different deployment scenarios or future screening requirements.

In the following sections, I break down how each subsystem (hardware, sensing algorithms, software architecture, and user interface) was designed, implemented, and evaluated as part of this project.

Design constraints that drove everything

Before choosing sensors, models, or materials, the most important step in this project was defining the constraints. Unlike a lab-only prototype, this kiosk was designed with real-world deployment in mind. Every technical decision, from hardware layout to algorithm selection, was shaped by a small set of non-negotiable constraints.

1. Minimizing Human Contact

The primary objective of the kiosk was to reduce close human interaction during health screening. Manual temperature checks and supervised screening introduce repeated contact between staff and users, increasing exposure risk.

This constraint directly influenced several design choices:

- Preference for contactless or low-contact sensing wherever possible

- Automated guidance to eliminate the need for trained operators

- Enforced sanitization as part of the screening workflow

While fully contactless sensing is attractive, it is not always reliable in practice. For this reason, the kiosk adopts a mixed sensing strategy, combining contactless measurements (vision and thermal imaging) with brief, controlled contact (fingertip PPG) when accuracy demands it.

2. Throughput and Time per User

Screening systems deployed in public spaces must process users quickly. Long interactions lead to queues, frustration, and ultimately abandonment of the system.

This constraint ruled out:

- Long signal acquisition windows

- Computationally heavy models that cannot run in real time

- Sequential processing of independent measurements

Instead, the system was designed to:

- Run multiple sensing pipelines in parallel

- Provide real-time feedback to keep the user engaged

- Complete all screening steps within a single, continuous interaction

The focus was not just on accuracy, but on accuracy per second of user time.

3. Accuracy vs. Deployability

Clinical gold-standard measurements often require trained personnel, invasive sensors, or long acquisition times. While highly accurate, these approaches are fundamentally incompatible with self-service kiosks.

This project explicitly prioritizes deployable accuracy over theoretical optimality:

- Infrared and thermal sensors instead of rectal or oral thermometry

- Photoplethysmography instead of ECG for pulse rate estimation

- Machine learning models optimized for robustness rather than peak benchmark scores

Wherever possible, measurements were evaluated against established gold standards, but the final system favors methods that can operate reliably in uncontrolled public environments.

4. Accessibility and Usability

A screening kiosk is only effective if it can be used by everyone. Many healthcare kiosks in existing literature overlook accessibility, despite well-established standards.

From the outset, the kiosk was designed to:

- Comply with ADA guidelines for physical reach and height

- Follow WCAG principles for visual contrast, feedback, and interaction flow

- Provide clear visual and audio cues to guide users

These requirements influenced physical dimensions, sensor placement, screen size, interface layout, and even color choices. Accessibility was treated as a core design constraint, not a post-hoc addition.

5. Cost and Economic Viability

Finally, the kiosk needed to make economic sense. A system that is accurate but prohibitively expensive will never see real deployment.

This constraint affected:

- Sensor selection and redundancy

- Material choices for the enclosure

- Preference for commodity hardware over specialized medical equipment

Together, these constraints shaped the kiosk.

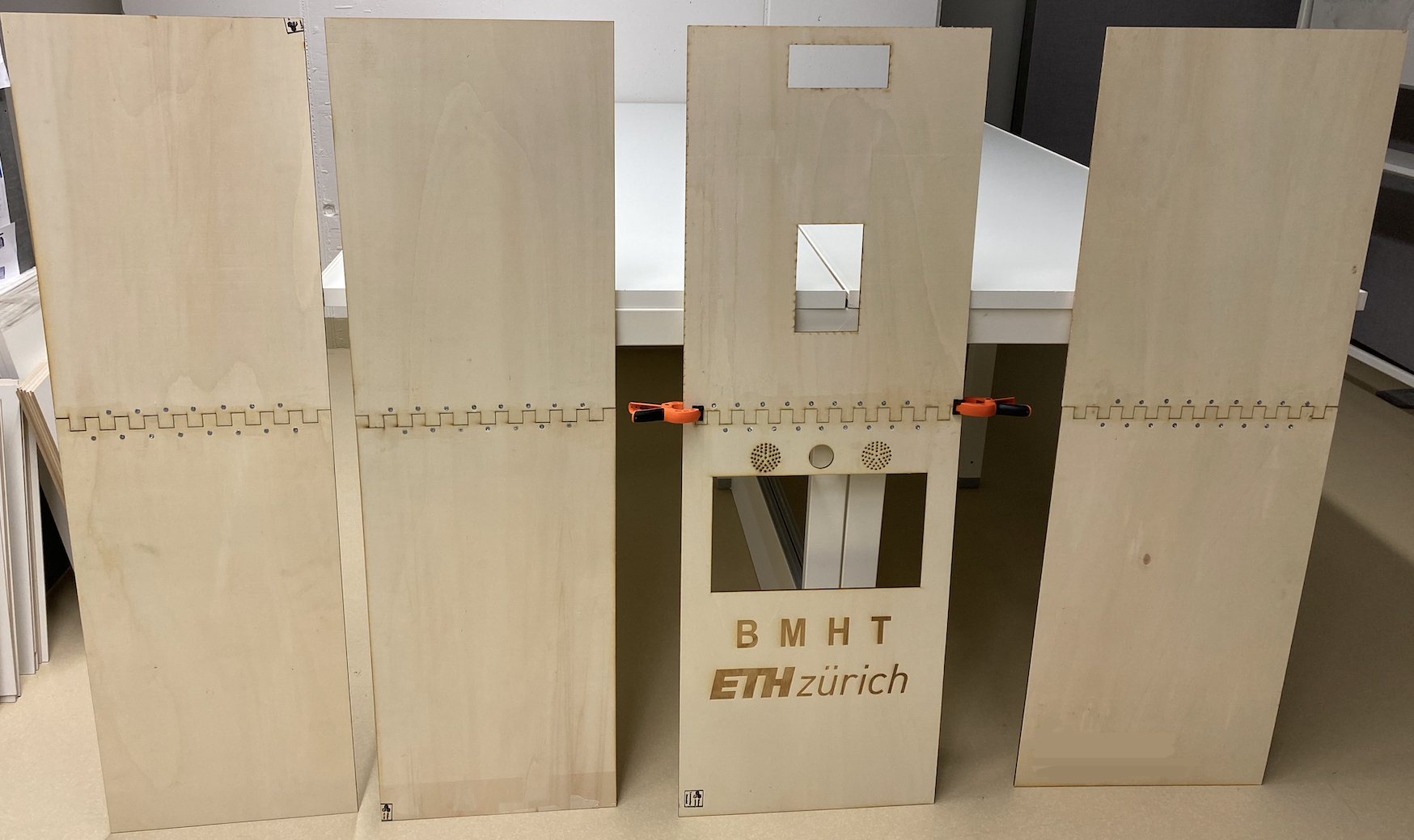

Hardware Design: CAD to Physical Kiosk

The kiosk was designed as a self-contained, freestanding system that balances accessibility, manufacturability, and rapid iteration. Rather than treating the enclosure as a passive shell, the physical design was tightly coupled with sensing, user interaction, and accessibility requirements.

CAD Design

The full kiosk was modeled in CAD to determine:

- Screen height and reach in accordance with accessibility guidelines

- Sensor placement for consistent line-of-sight and thermal measurements

- Internal volume for electronics, wiring, and airflow

This upfront CAD work allowed component placement, user posture, and interaction flow to be evaluated before fabrication.

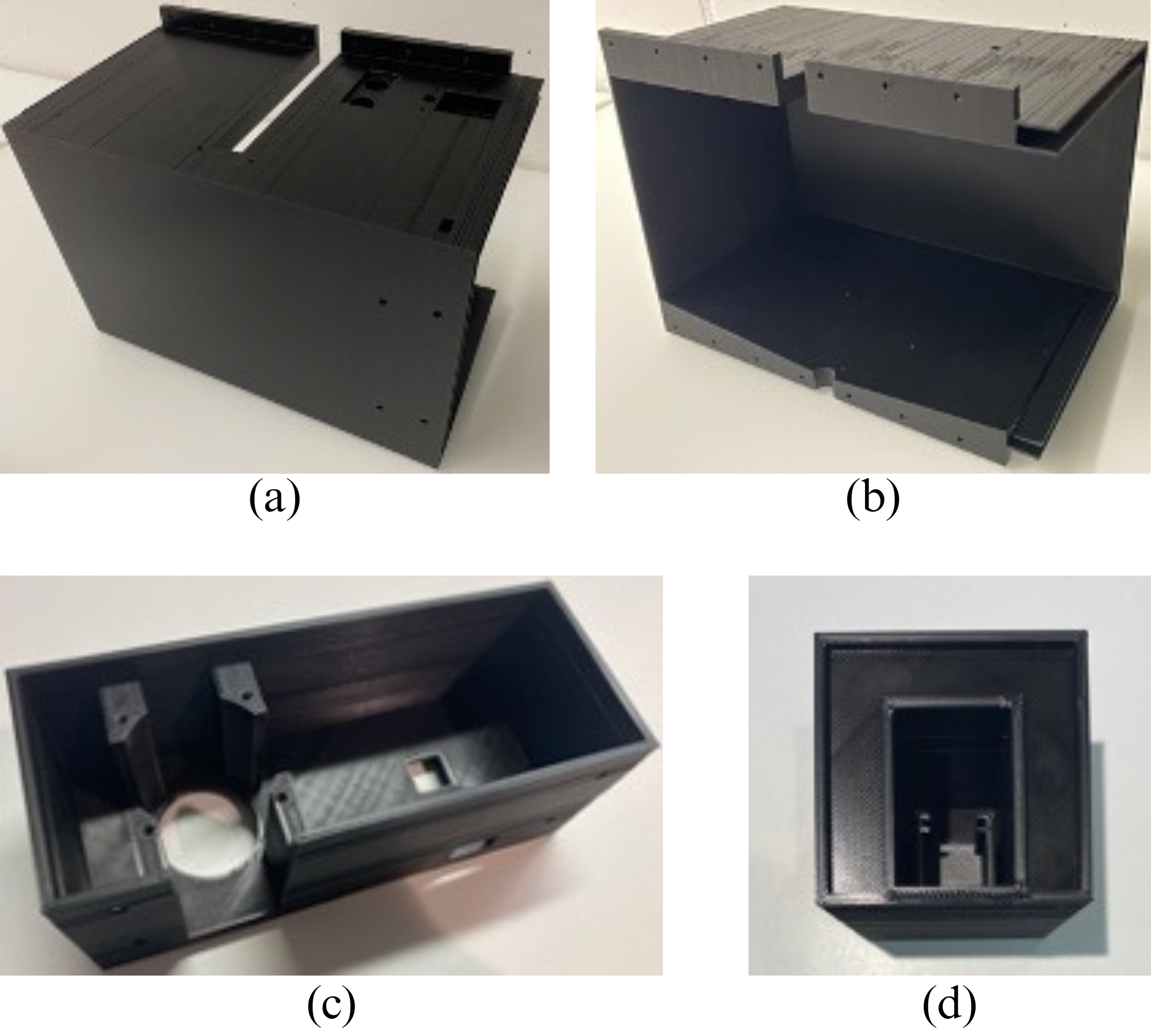

Fabrication and Assembly

To keep the system inexpensive and easy to modify, the enclosure was built using:

- Laser-cut plywood panels for the main structure

- 3D-printed parts for sensor housings, hand trays, and internal mounts

This hybrid approach enabled fast iteration: structural changes could be made by updating CAD files and re-cutting or re-printing individual components rather than rebuilding the entire kiosk. Each sensing module (RGB camera, thermal/infrared sensing, PPG sensor, and motion sensor) was housed in a dedicated enclosure.

Electronics Design

The kiosk is controlled by a Raspberry Pi acting as the central compute and coordination unit. All sensing, user interaction, and control logic originate from the Raspberry Pi, with peripheral microcontrollers used only where strict timing or I/O isolation is required.

Central Controller (Raspberry Pi)

The Raspberry Pi handles:

- Sensor orchestration and data acquisition

- Image capture and processing

- Signal processing and inference

- GUI rendering and workflow control

An Raspberry Pi High Definition Camera is connected directly to the CSI port and is used for both mask detection and remote photoplethysmography (rPPG). This interface was selected to ensure low-latency, high-bandwidth image acquisition with minimal CPU overhead.

A PIR motion sensor is connected to a GPIO pin and is used to detect the presence of a new user. This signal is used to transition the system from an idle state into an active screening workflow.

I²C Sensor Bus and Address Management

Physiological and thermal sensing devices are connected to the Raspberry Pi via the I²C bus:

- Two thermal cameras

- One infrared temperature sensor

- One fingertip PPG sensor

Both thermal cameras share the same fixed I²C address. To resolve this address conflict, an additional GPIO line from the Raspberry Pi is used to control sensor power, ensuring that only one thermal camera is powered and active on the bus at any given time. This approach avoids the need for external I²C multiplexers while maintaining deterministic sensor selection.

Peripheral Control Microcontroller

A secondary Arduino-based microcontroller is used to handle time-critical peripheral control and user feedback elements. This microcontroller is responsible for:

- Driving all RGB LED indicators

- Controlling a relay connected to a sanitizer pump

- Reading an ultrasonic distance sensor for hand detection

RGB LED strips are used as an accessibility aid, dynamically indicating which part of the kiosk the user should interact with at each step of the workflow (e.g., blinking LEDs around the PPG sensor when finger placement is required).

The sanitizer pump is actuated through a relay, triggered when the ultrasonic sensor detects the user’s hands within a predefined distance threshold.

Inter-Controller Communication

The Arduino communicates with the Raspberry Pi over a UART interface. The Raspberry Pi acts as the master controller, issuing commands to:

- Change RGB LED states

- Trigger sanitization

- Enable or disable peripheral actions

The Arduino returns status signals (e.g., hand detected, action complete), allowing the Raspberry Pi to synchronize peripheral actions with the main screening workflow.

Sensing Stack & Algorithms

The kiosk integrates multiple sensing modalities, each targeting a specific physiological or behavioral signal. Each subsystem was designed to operate independently, with minimal assumptions about user behavior or environmental conditions, and to produce outputs that could be synchronized at the decision layer.

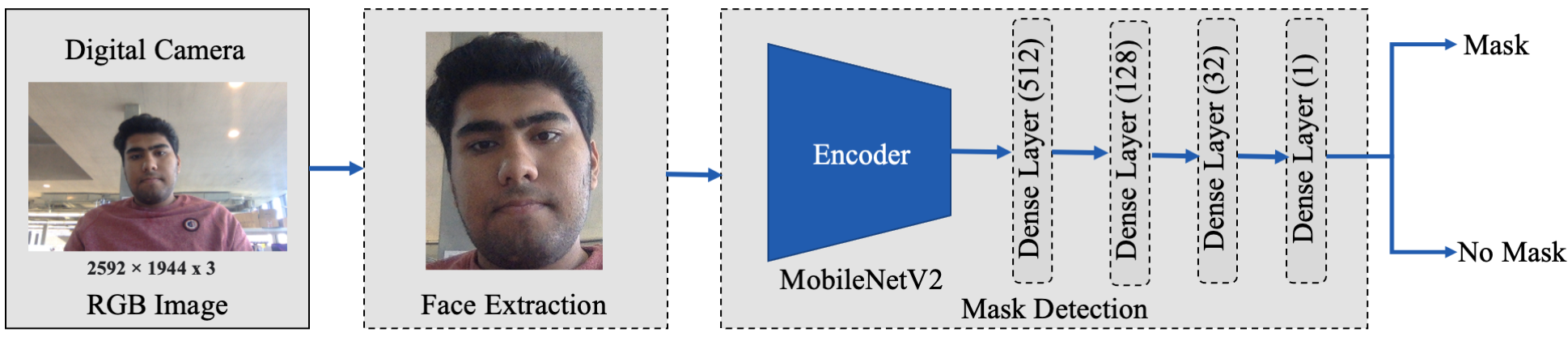

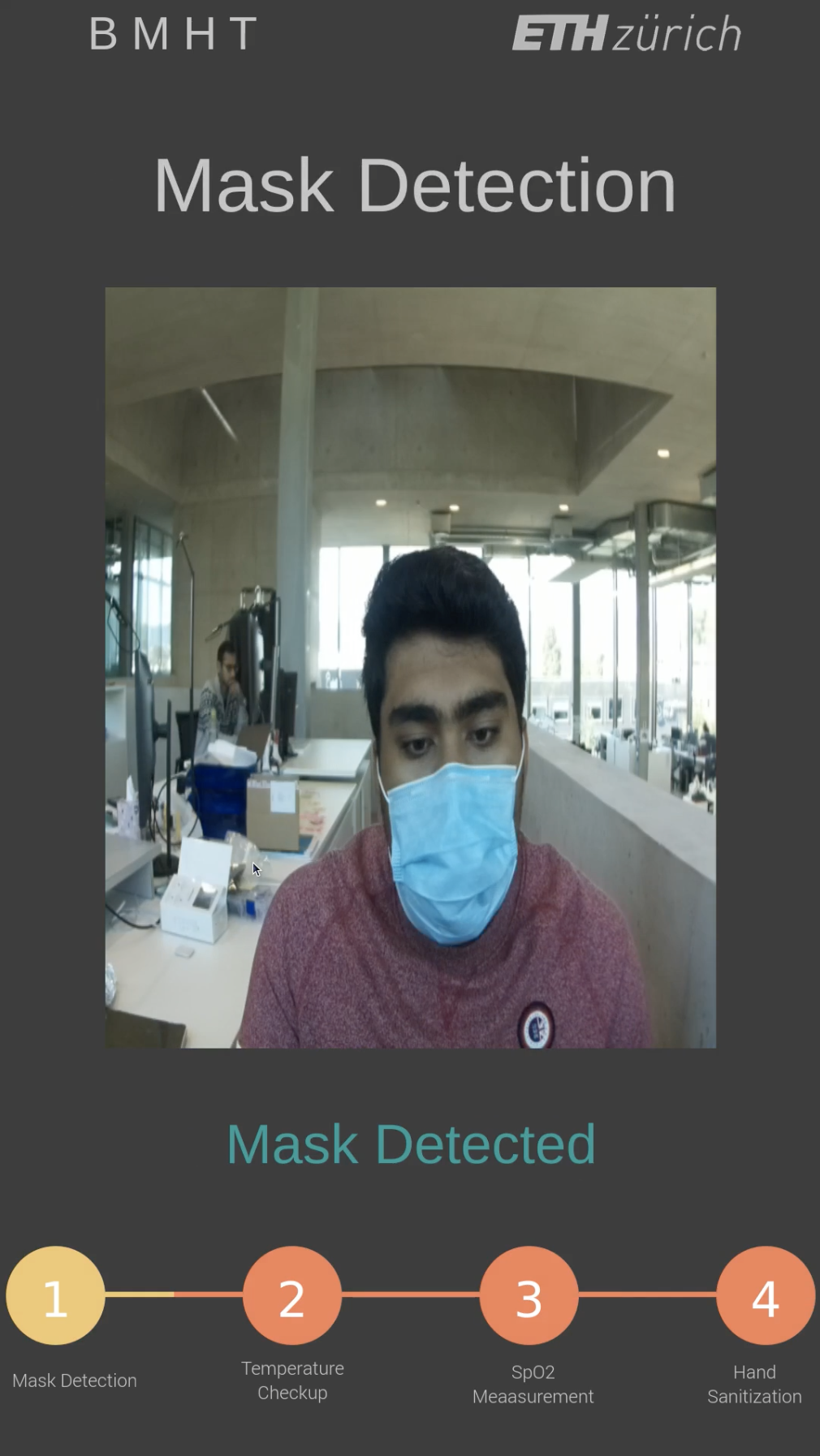

Mask Detection (RGB Vision)

Mask compliance is detected using an RGB camera mounted above the display, aligned to capture a frontal facial view during user interaction.

The pipeline consists of:

- Face detection and region extraction

- Binary mask classification using a lightweight convolutional neural network

- Temporal smoothing across consecutive frames to reduce flicker and false positives

The model was trained on a curated dataset containing masked and unmasked faces under varying lighting conditions, camera angles, and occlusions. Model optimization focused on inference speed and robustness rather than maximizing benchmark accuracy, enabling real-time execution on consumer-grade hardware.

Output from this subsystem is a confidence score indicating mask compliance, which gates progression to subsequent screening steps.

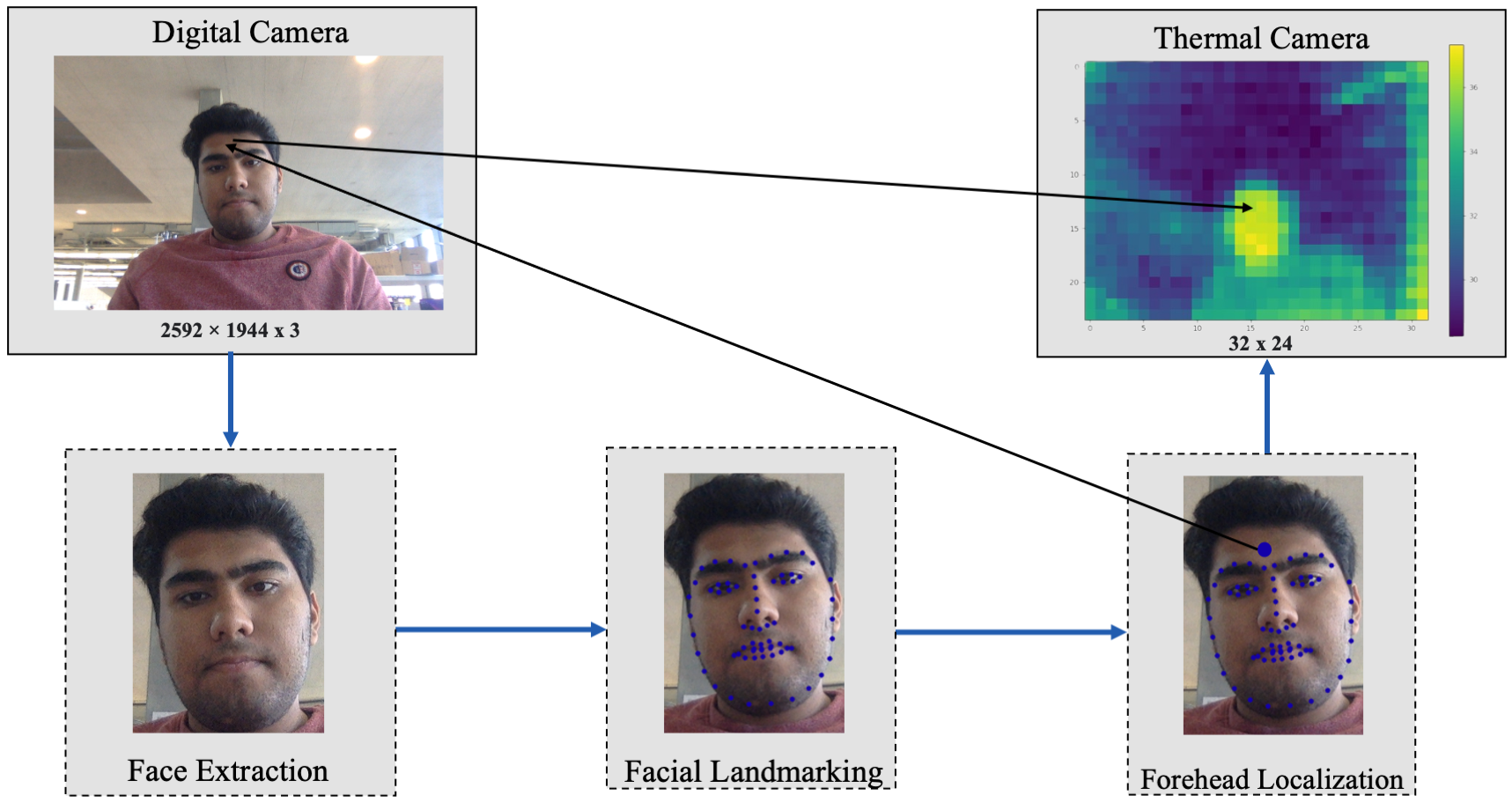

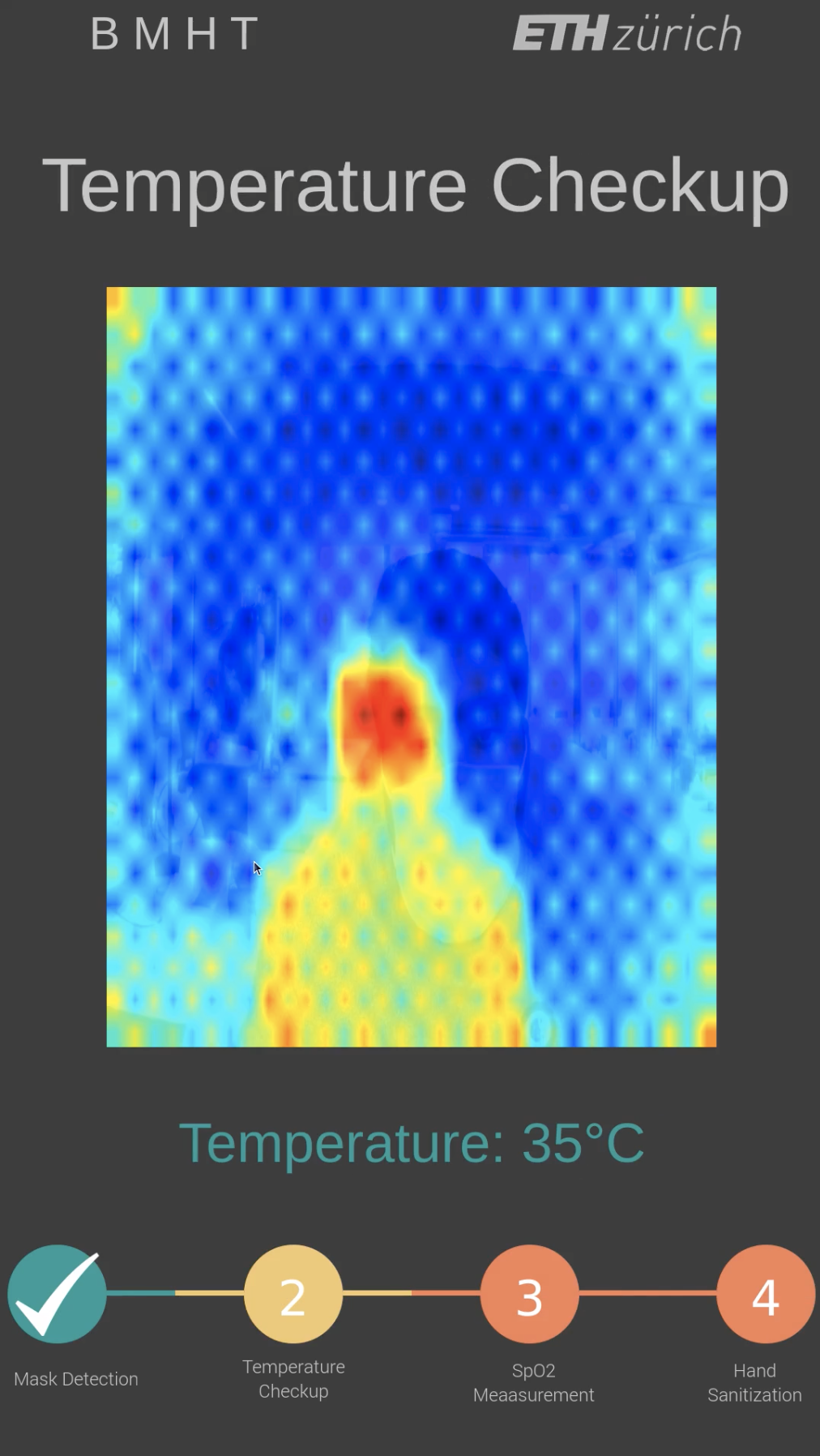

Body Temperature Measurement (Thermal + Infrared)

Body temperature is estimated using a combination of:

- A thermal camera for spatial temperature distribution

- An infrared temperature sensor for localized point measurements

Facial temperature is estimated by identifying the forehead region in the thermal frame, while hand temperature is captured when the user places their hand inside the designated tray. These measurements are corrected for environmental variation and sensor noise through calibration offsets determined during testing.

The dual-sensor approach reduces sensitivity to improper positioning and ambient temperature fluctuations, which are common failure modes in single-sensor systems.

Pulse Rate and SpO₂ (PPG and rPPG)

Physiological monitoring is performed using two complementary approaches.

Contact-based PPG:

A fingertip pulse oximeter provides direct photoplethysmographic measurements used to estimate pulse rate and blood oxygen saturation. The raw PPG signal is filtered to remove motion artifacts and baseline drift before peak detection and BPM estimation.

Camera-based rPPG:

In parallel, pulse rate is estimated remotely using an RGB camera via remote photoplethysmography. The rPPG pipeline consists of:

- Face detection and ROI selection

- Extraction of mean RGB intensity signals over time

- Temporal filtering and windowing

- Blood Volume Pulse (BVP) estimation using signal processing methods

- Frequency-domain analysis for BPM estimation

Multiple rPPG algorithms were evaluated, including chrominance-based and plane-orthogonal-to-skin methods, with selection driven by robustness to motion and illumination changes rather than raw accuracy.

The contact-based PPG serves as a reliability anchor, while rPPG provides a contactless estimate and redundancy under partial sensor failure.

Synchronization and Data Flow

Each sensing module produces time-stamped outputs that are buffered and synchronized by the central controller. This design allows:

- Parallel execution of independent sensing pipelines

- Graceful degradation if one modality fails

- Consistent decision-making despite variable acquisition times

No single sensing modality is treated as authoritative; instead, each contributes a bounded-confidence signal to the overall screening process.

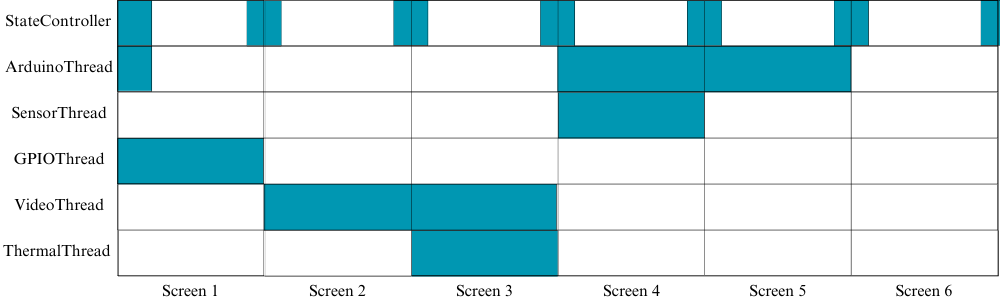

Software Architecture and Parallelization

The kiosk software is implemented as a multi-threaded system on Linux, with the Raspberry Pi acting as the central coordinator. The architecture is designed to ensure low end-to-end latency, deterministic user flow, and independence between sensing pipelines.

Process and Thread Model

The application runs as a single primary process with multiple long-lived threads, each responsible for a specific subsystem:

- Camera acquisition and vision inference thread

- Thermal sensing thread

- PPG/rPPG acquisition and signal processing thread

- GUI event loop thread

- Peripheral control and I/O thread (UART, GPIO)

Threads are initialized at startup and remain active throughout execution. No sensing task is spawned dynamically to avoid startup latency during user interaction.

Parallel Sensing Pipelines

Independent sensing subsystems operate concurrently:

- Mask detection runs continuously once a face is detected in the camera stream

- Thermal measurements are triggered asynchronously based on workflow state

- PPG and rPPG acquisition run in parallel, each with independent buffering and windowing

This design avoids sequential blocking (e.g., waiting for physiological signals before completing vision-based checks) and minimizes total screening time.

Synchronization and Shared State

Inter-thread coordination is handled through:

- Thread-safe shared state variables

- Event flags signaling completion or failure of each screening step

- Mutex-protected buffers for sensor outputs

Each sensing thread writes its result to a bounded buffer along with a timestamp and confidence value. The central controller thread consumes these results and enforces ordering constraints defined by the screening state machine.

State Machine–Driven Workflow

The kiosk workflow is implemented as a deterministic finite state machine. State transitions are driven exclusively by:

- Sensor completion signals

- Validity checks on acquired data

- User interaction events

No GUI action directly triggers sensing or actuation. All control flows through the state machine, ensuring reproducible behavior and preventing race conditions between UI events and hardware actions.

GUI and Responsiveness

The graphical user interface runs in its own thread using an event-driven loop. All long-running operations (inference, signal processing, I/O) are explicitly excluded from the GUI thread.

The GUI subscribes only to high-level state updates and renders:

- Current workflow step

- Progress indicators

- Error or repositioning prompts

This separation guarantees that UI responsiveness is unaffected by sensor acquisition delays or computational load.

Peripheral Coordination

UART communication with the Arduino is handled in a dedicated I/O thread. Commands are issued asynchronously based on state machine transitions (e.g., enable LEDs, trigger sanitizer). Status messages from the Arduino are parsed and forwarded to the controller thread without blocking other subsystems.

Fault Handling and Degradation

Each sensing thread performs internal validity checks (e.g., signal quality, timeout thresholds). On failure:

- The thread reports an invalid result to the controller

- The workflow either retries the step or bypasses the modality

- The system continues operation without deadlock

No single sensor failure can stall the entire screening pipeline.

User Experience & Accessibility

The user interaction layer is designed to minimize cognitive load and prevent incorrect usage while maintaining compliance with established accessibility standards.

Interaction Model

User interaction follows a strictly guided, step-based flow enforced by the system state machine. At any time, only one valid user action is permitted. All other inputs are ignored to prevent invalid transitions.

Feedback mechanisms include:

- Visual prompts on the display

- RGB LED indicators highlighting the active interaction region

- Audio cues for step completion and error conditions

Users are never exposed to raw sensor data or intermediate states.

Accessibility Constraints

Physical and software accessibility requirements were treated as hard constraints during design.

- Kiosk height, reach envelope, and sensor placement follow ADA-recommended ranges

- Interactive elements remain within forward-reach limits for wheelchair users

- High-contrast UI elements and large fonts are used consistently

- Timeouts are minimized and explicitly signaled

RGB lighting is used to spatially guide users (e.g., blinking LEDs around the PPG sensor during finger placement), reducing reliance on textual instructions.

No fine motor actions or prolonged postures are required at any stage of the interaction.

Deployment

The kiosk is deployed as a standalone, continuously running system intended for unattended operation in public environments. Upon boot, the system initializes all sensing threads, peripheral interfaces, and the GUI, then enters an idle state awaiting user presence.

Runtime States

The deployed system operates through a fixed set of runtime states:

- Idle (no user detected)

- User detected (PIR-triggered)

- Mask verification

- Temperature measurement

- Physiological sensing (PPG / rPPG)

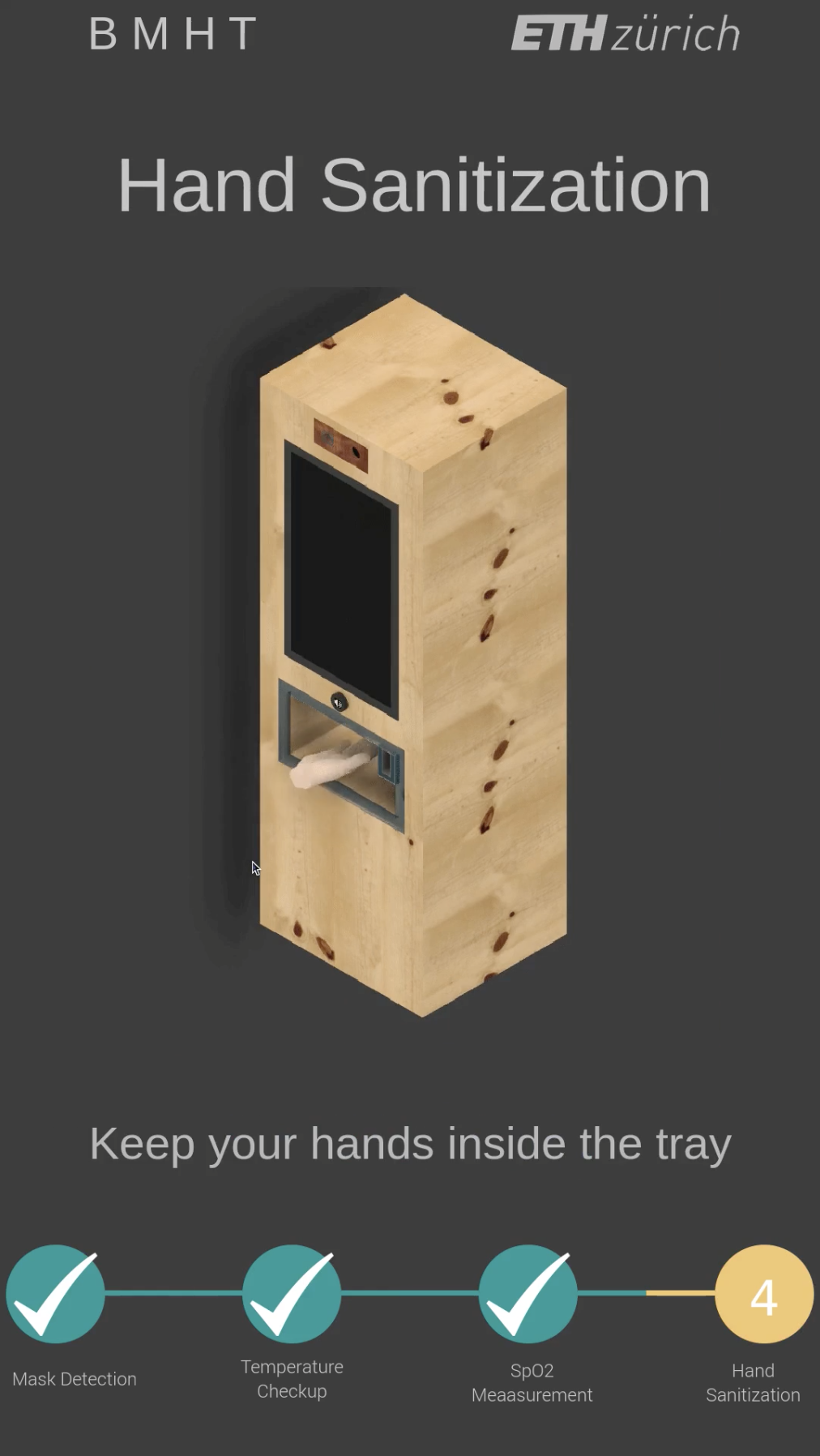

- Sanitization

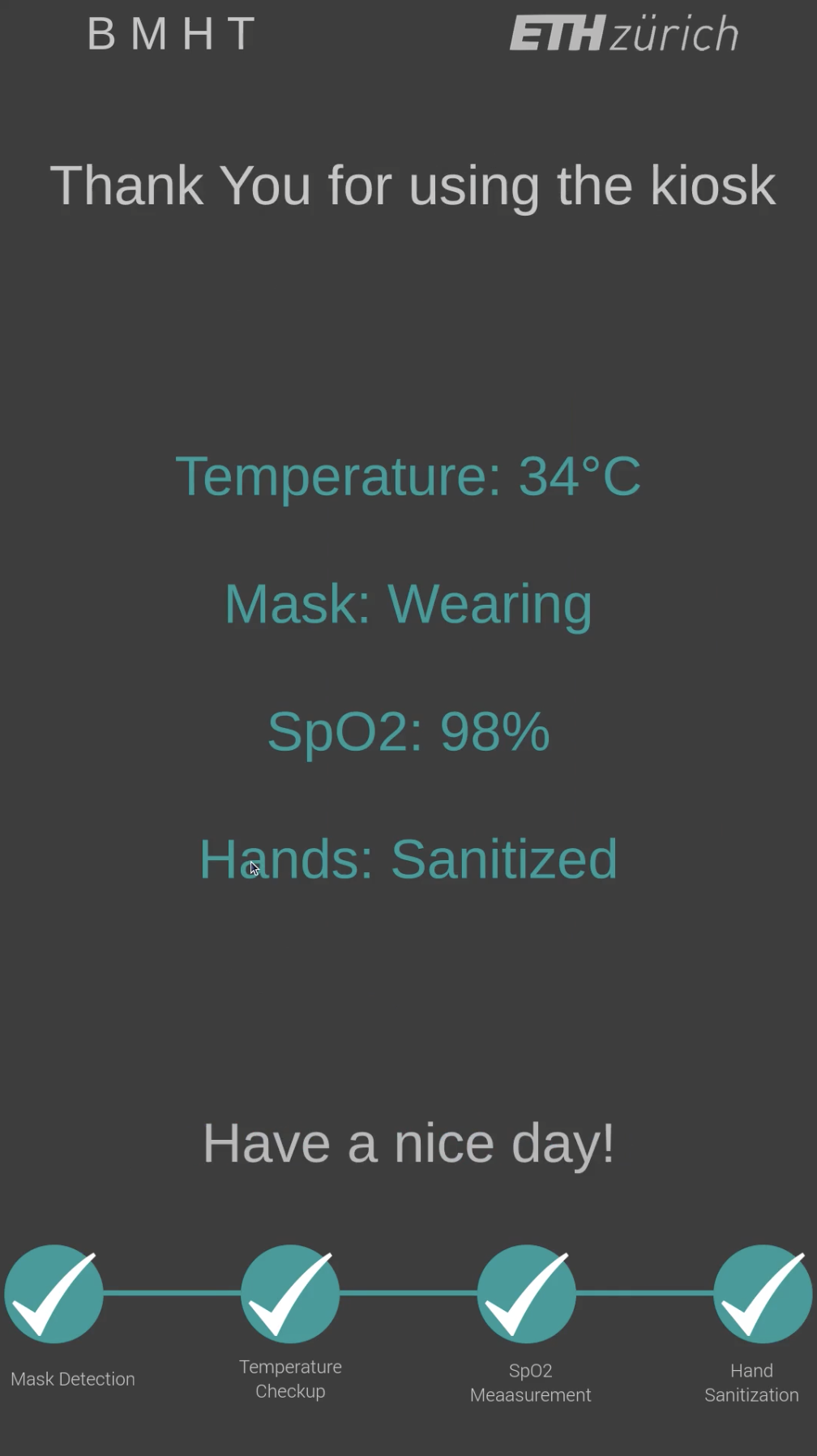

- Screening result display

State transitions are governed exclusively by the central controller and are not directly user-triggered.

Graphical User Interface

The GUI provides step-specific guidance synchronized with the workflow state machine. Each screen maps to a single system state and exposes only the required interaction.

UI characteristics:

- Full-screen, single-task views

- Large, high-contrast visual elements

- Minimal text, icon-driven instructions

- Explicit progress indicators showing screening stage completion

UI–Hardware Coupling

During deployment, the UI is tightly synchronized with physical feedback mechanisms:

- RGB LEDs are activated only for the currently relevant interaction region

- Audio cues signal state transitions and completion events

- Peripheral actuation (e.g., sanitizer pump) is visually confirmed through UI state changes

This coupling ensures that users receive redundant feedback across visual, spatial, and auditory channels, reducing ambiguity and misuse.

Error Handling and Recovery

The deployed UI includes explicit handling for common failure modes:

- Incorrect positioning

- Incomplete sensor contact

- Timeouts during physiological acquisition

When a failure is detected, the system either re-prompts the user with corrective instructions or safely resets to an earlier state. No undefined UI states are exposed to the user.

Deployment Characteristics

The final deployed system:

- Requires no external network connectivity for operation

- Automatically resets to the idle state after each completed interaction

- Can operate continuously without manual intervention

All UI assets and configuration parameters are packaged locally, ensuring predictable behavior across deployments.

User Interface Screenshots

Conclusion

This project demonstrates the design and deployment of a fully automated COVID-19 screening kiosk that integrates vision-based compliance checks, thermal sensing, and physiological monitoring into a single, deployable system. The kiosk was engineered end-to-end, spanning hardware design, embedded electronics, real-time software architecture, sensing algorithms, and user-facing deployment.

The final system is built entirely from commodity hardware, with a rough total cost in the low four-figure USD range, making it economically viable for deployment in high-traffic public environments. The modular architecture allows individual sensing components to be replaced or extended without redesigning the entire system.

I am grateful to Prof. Moe Elgendi and Carlo Menon for their guidance and support, and to my colleagues at the BMHT, ETH Zurich.